“Astounded,” shocked” and “dismayed” were some of the adjectives used by a vast array of experts to describe the Federal Communications Commission’s April decision to approve an application by Ligado Networks. Government testing had shown that Ligado’s operations would interfere with reception of GPS signals for many users. The application had been strenuously opposed by the executive branch, particularly the departments of Defense and Transportation, and myriad industry and citizen groups.

Before the decision was announced most had considered the issue safely dead. Yet, the FCC approved the application in the face of this overwhelming opposition.

By way of explanation, the commission said its technical experts had concluded that interference with GPS signals was unlikely. And if it did occur, it would be very minor. Unfortunately, they offered no analysis or technical evidence to support the claim.

This left many scratching their heads as to how government experts at the FCC could come up with findings so different from government experts at the departments of Defense and Transportation.

RELATED

There is a growing school of thought that the answer to “How could they do that?” is not a matter of realpolitik or commercial scheming. Rather, it lies in the fundamentally different ways communications and navigation systems use the airwaves. And that the communications engineers at the Federal Communications Commission unconsciously used inappropriate criteria in their analysis.

This seems to be the thinking behind a provision in the Senate version of the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act. It directs tasking “the National Academies of Science and Engineering for an independent technical review of the order to provide additional technical evaluation to review Ligado’s and DOD’s approaches to testing.”

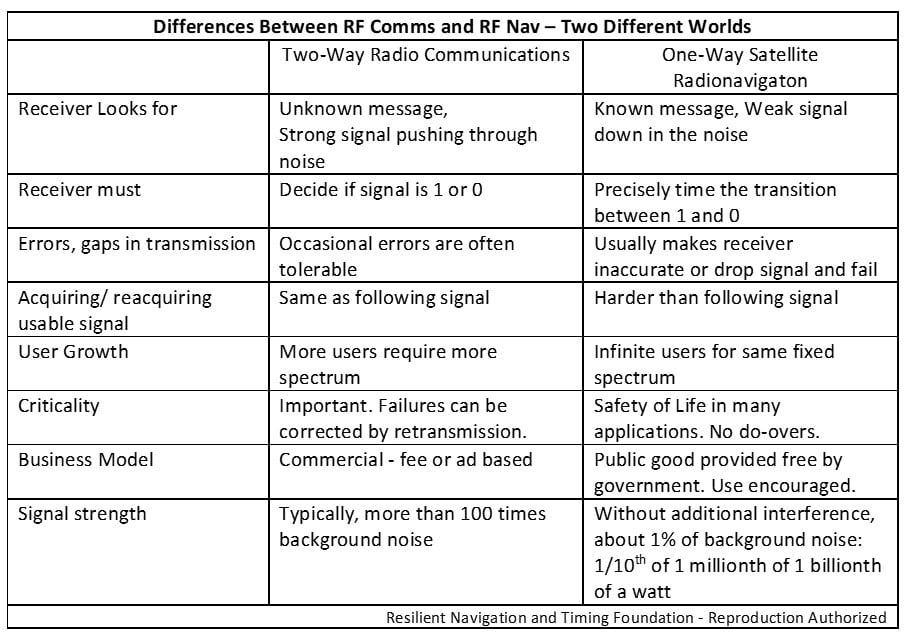

“GPS and communications systems are entirely different,” said Brad Parkinson of Stanford University, the original chief architect of GPS. “Communications is about strong signals with an unknown message pushing through the background noise so the receiver can read the ones and zeros. GPS receivers look for a known, but very weak messages down within the background noise. They precisely measure the time between the ones and zeros. Typically, GPS receivers resolve time of arrival to 1 billionth of a second or better.”

Another important difference is that some interference is tolerable in communications. A bit of static, or even a momentary break, often does not prevent the message from getting through. And in two-way communications, like a cellphone call, one party can just ask for the message to be repeated.

Not so in navigation. Long experience has shown that one of the first effects of interference with many navigation receivers is hazardously misleading information. The receivers “wander off” before they cease giving information altogether. And once an interference source knocks it offline, a GPS receiver will often not be able to function again until the source is long gone.

GPS advocates like to point out: “There aren’t any do-overs in navigation. No ‘say again’ or ‘please repeat that.’ ”

And while both communications and navigation are very important, navigation has a greater and more immediate impact on safety of life in far more instances. Disruptions in navigation signals threaten all forms of transportation, much of it at high speed. Examples documented in the last 18 months have included a passenger aircraft nearly hitting a mountain, and the crash of a large drone that could have injured or killed someone on the ground.

This impact on safety of life has compelled the Department of Transportation to include a safety buffer when evaluating systems that might interfere with GPS signals. This helps ensure navigation is never impacted. This safety buffer is much like weight limits established for vehicles crossing a bridge. The limits help ensure the bridge never approaches its breaking point.

The criteria used by the engineers at the FCC seems more like what they might have used when evaluating possible interference with a communications system. “A little” interference could be acceptable.

A little interference in your car radio could mean a some static while you are jamming to the oldies.

In tests, interference with GPS has driven some cars off the road.

To be fair, most of the FCC tasking and work since it was established in 1934 has focused on communications issues. Spectrum management has likely been viewed as a tool in support of that mission, rather than a goal in and of its own.

Yet, in 2020, spectrum is increasingly used by far more applications and in diverse ways that are often very difficult to call “communications.” GPS, radar, advanced sensors, space-based Earth observation, radar altimeters for aircraft, intelligent and autonomous transportation systems, WiFi, weather forecasting — they all use spectrum and/or depend upon a stable and predictable spectrum environment. And as technologies continue to evolve, this will only increase.

Perhaps it is time to recharter the FCC as the “Federal Spectrum Commission.” It would undoubtedly still have to make hard, perhaps controversial, decisions. But perhaps it would be more likely to fully appreciate the needs of all radio frequency users, and publish technically convincing analyses to support their decisions and reassure stakeholders.

Dana A. Goward is the president of the Resilient Navigation and Timing Foundation.