WASHINGTON — In January 2017, one of the government’s newest weather satellites picked up the most bizarre signal: a wildfire moving at breakneck speeds across the Atlantic Ocean.

Now, wildfires don’t spread across the ocean, and they certainly don’t move at the pace being reported. What was going on?

It turns out the satellite ― one of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s GOES-R series — had accidentally detected a rocket launch off the Florida coast, mistaking the fiery exhaust of a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket for a wildfire.

“It was actually — honest — by accident, where we saw a rocket launch on the East Coast of Florida,” L3Harris Technologies President of Space Systems Bill Gattle told C4ISRNET. “Our weather sensor actually sent a trigger and said there’s a fire — our weather sensor actually tracks forest fires or hot spots — and today there’s this fire moving very fast across the Atlantic and so they ought to go put it out.”

RELATED

That accidental discovery set L3Harris on a multiyear journey to transform its infrared weather sensor technology into a missile detecting capability for the U.S. military. The move would have the potential to bring in billions: The U.S. Air Force doled out $1.86 billion for just two missile warning satellites in 2014. However, the competition is tight.

Traditionally, the Air Force built one missile warning constellation at a time with limited overlap, with only a few companies awarded massive contracts. Lockheed Martin is the prime contractor for all four geosynchronous satellites that make up the Space-Based Infrared System, as well as the final two expected to launch later this year. Northrop Grumman was the major subcontractor, building the satellites’ sensors.

L3Harris isn’t exactly a lightweight in DoD contracting — it’s No. 9 on the Defense News Top 100 list of global defense companies and brought in nearly $14 billion in defense revenue in 2019. For perspective, Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman secured about $57 billion and $29 billion in defense revenue, respectively.

Entering the competition

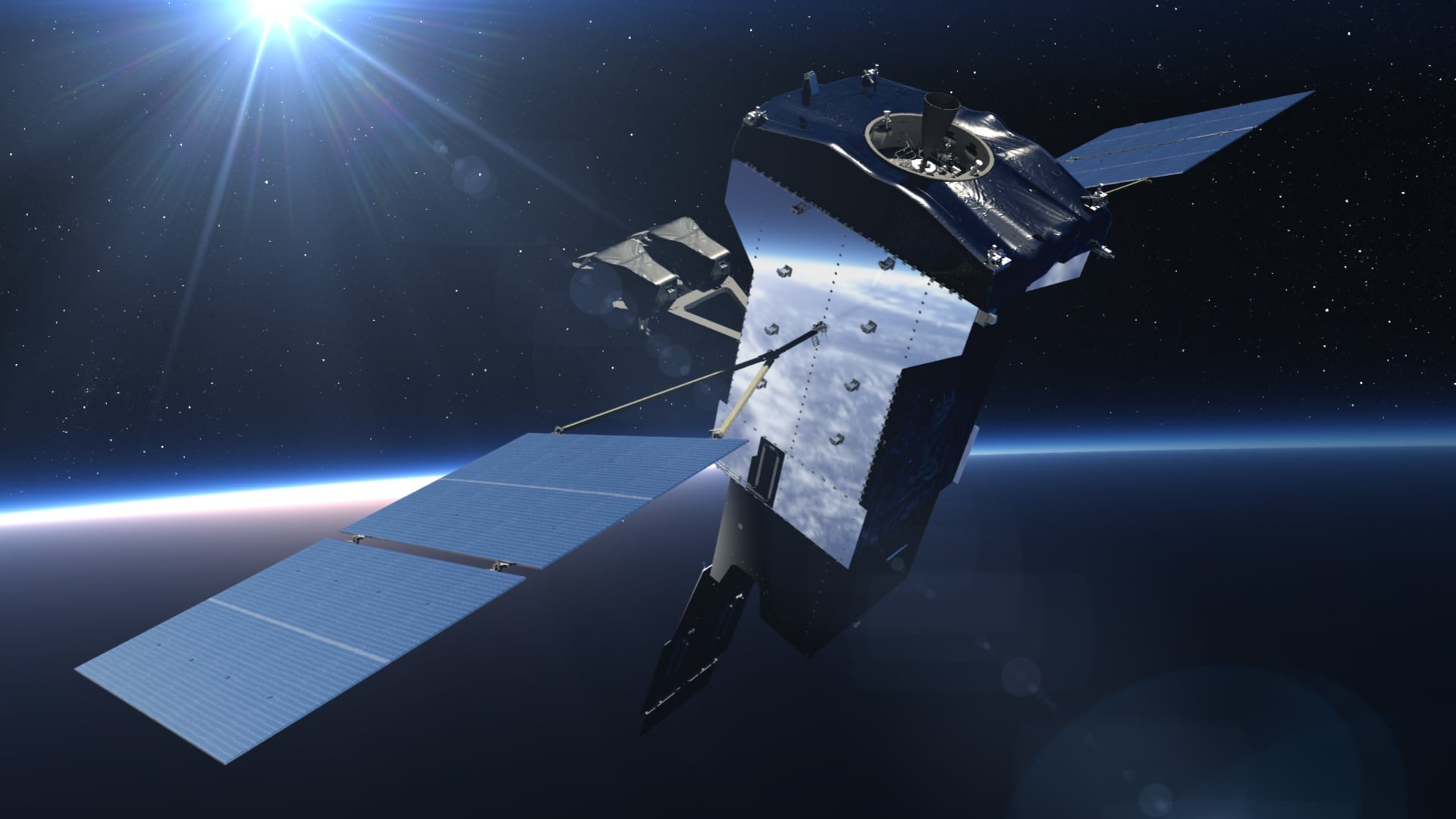

After the decision to shift its weather technology to missiles, L3Harris’ immediate plan was to compete to build SBIRS’ successor, the Next Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared. Like SBIRS, Next Gen OPIR will be made up of a handful of satellites in geosynchronous orbit with two more in highly elliptical orbit. L3Harris faced the biggest defense contractors in the business. But with billions of dollars in contracts at stake, the company went for it.

Starting in 2018, L3Harris began investing “several millions of dollars” into the effort, according to a company spokesperson, including building a new payload production facility in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

The company quickly realized it needed to refine its weather sensor to meet the military’s needs.

“When you’re doing a weather mission, you’re looking at the Earth, and you’re scanning the Earth for weather, but weather doesn’t move nearly as fast as a missile does,” explained Gattle. “We had to get to where we could actually track a missile very fast. So our sensor had to become much faster at tracking things.”

The company also had to invest in algorithms that can cut out background noise picked up by the sensor.

“You have to be very sensitive to what’s happening in the background when you’re seeing missiles. There’s a lot of noise, if you will, and [with] infrared there’s a lot of heat signature off the Earth. So you have to be able to distinguish if what you’re seeing is an airplane, a missile — what is it?”

The company fell short in its first attempt to break into missile tracking. The Air Force selected Lockheed Martin to build the three geostationary Next Gen OPIR satellites, while Northrop Grumman will build two more for highly elliptical orbits. At first, it might have seemed like the investment was for naught. L3Harris would have to wait years to compete for whatever satellites are added to or replace that constellation.

RELATED

However, growing concerns over hypersonic weapons from the Pentagon and Congress opened new doors for the company.

A hypersonic opportunity

The emergence of hypersonic weapons over the last few years poses a problem to America’s missile warning systems. When viewed from space, the weapons appear 10 to 20 times dimmer than traditional ballistic missiles, making it harder for satellites in geosynchronous orbit to pick them up. Because the weapons are maneuverable, they can theoretically move to avoid ground-based sensors. It became clear that the U.S. needed a new constellation of space-based sensors that could detect and track the new threat.

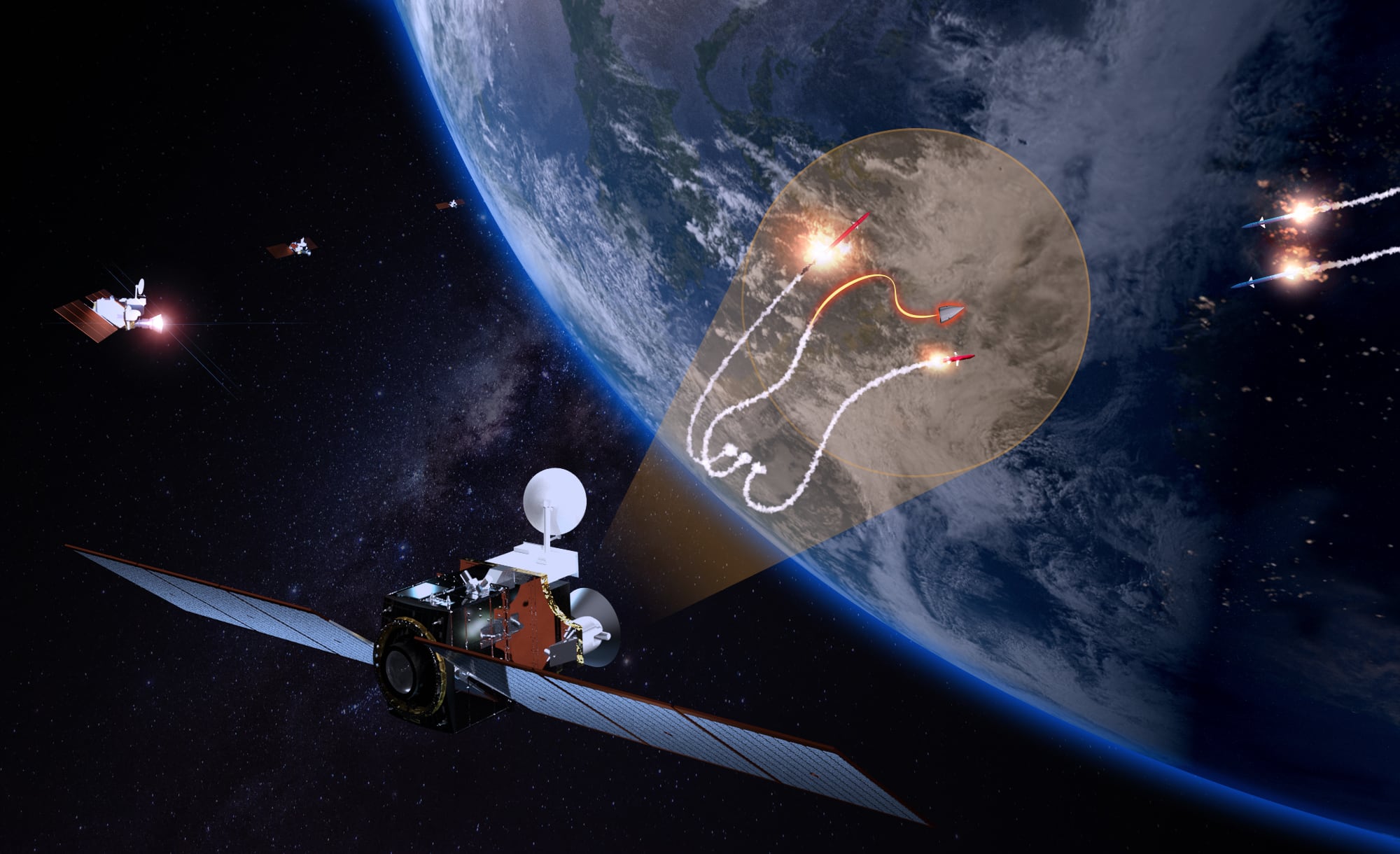

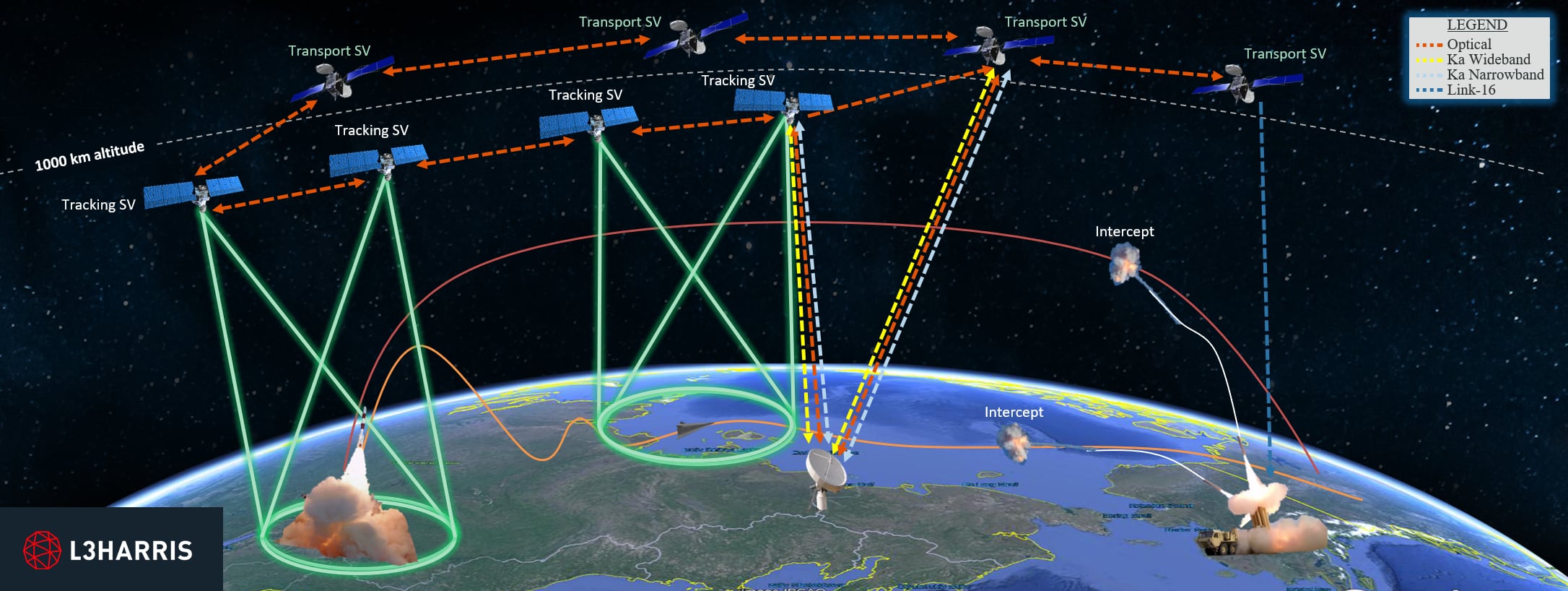

The solution that emerged is both simple and complex. Instead of relying solely on the exquisite sensors more than 22,000 miles above the Earth’s surface, the military will build a proliferated constellation located much closer to the planet’s surface in low Earth orbit — less than 1,200 miles up. From that lower vantage, it is easier for infrared sensors to pick up the hypersonic weapons, track them as they move around the globe, and provide the targeting data to destroy them.

This tracking effort effectively has three parts:

- A proliferated constellation with wide-field-of-view sensors in low Earth orbit that will pick up and track hypersonic weapons as they move around the globe.

- A data transport layer of satellites to connect the sensors on orbit and pass tracking data as the threat moves in and out of view of individual sensors.

- A smaller constellation with more sensitive, medium-field-of-view satellites that will provide the final targeting data to a fires solution.

The Space Development Agency is building those first two sections as part of its National Defense Space Architecture, a proliferated constellation in low Earth orbit that will eventually be made up of hundreds of satellites. The Missile Defense Agency will develop the medium-field-of-view satellites, known as the Hypersonic and Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor, or HBTSS. Meanwhile, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency is building Project Blackjack to demonstrate many of the technologies needed to make the entire system work.

RELATED

In October 2019, L3Harris got its first hint that it could crack the missile warning enterprise. MDA awarded the company a $20 million contract to design an HBTSS prototype, placing the business among heavyweights Northrop Grumman, Leidos and Raytheon.

Becoming a contender

A second win came months later in May 2020, when DARPA revealed L3Harris was in the running to build an electro-optical/infrared sensor for the Blackjack demonstration. To be clear, there was no direct path from a Blackjack contract to an actual program of record with either MDA or SDA.

Still, the parallels between the DARPA demonstration and those efforts were clear, and a Blackjack program contract could be seen as a pretty significant leg up for those competitions.

Regardless, L3Harris’ bid failed. The company’s proposal was too pricey, said Gattle, and the $37 million Blackjack payload contract went to Raytheon. In response, L3Harris invested to make sure it could build faster and present a more affordable solution. That would be key as the company prepared to bid on the SDA constellations.

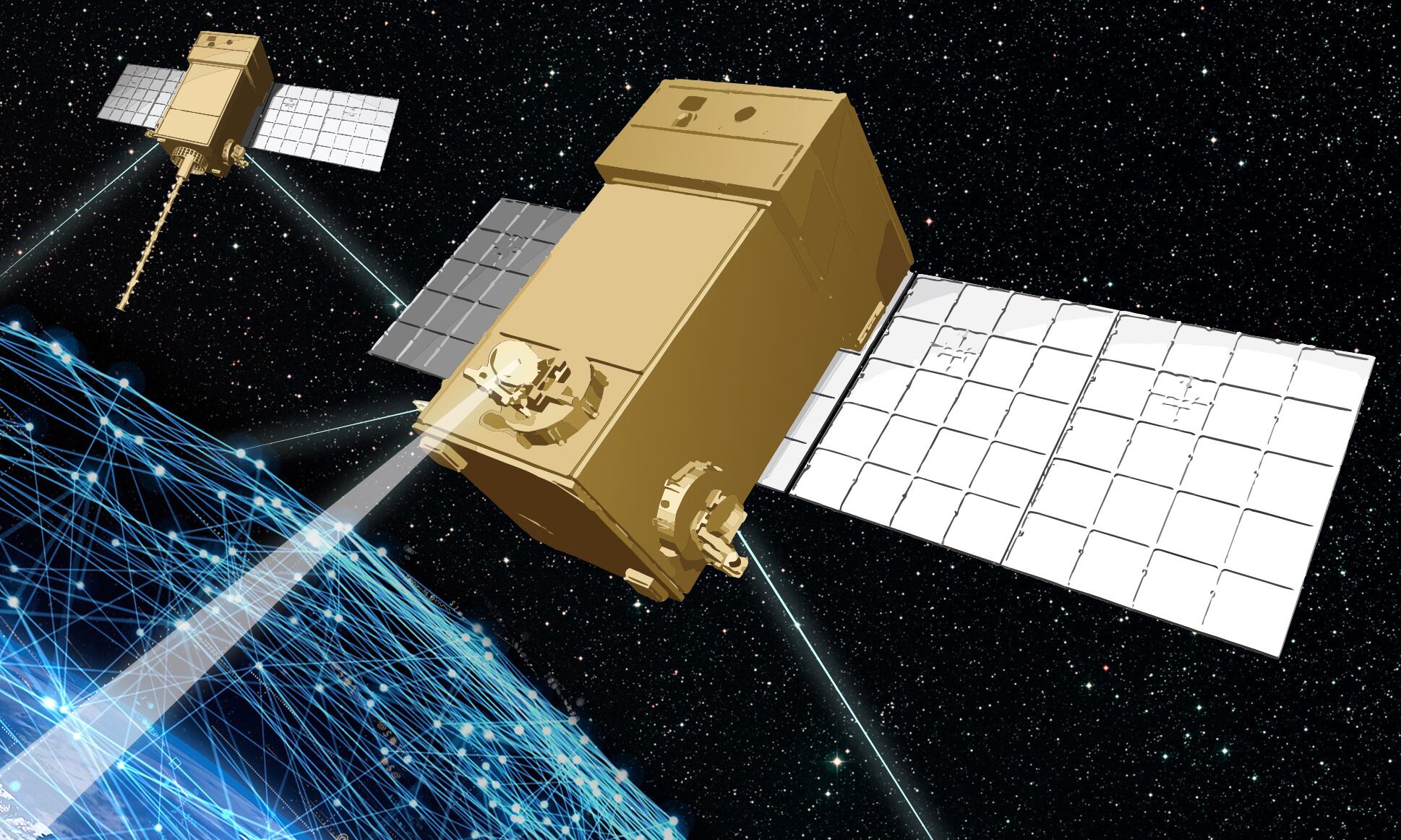

SDA released solicitations for its initial data transport layer and tracking layer satellites last May. At stake were four contracts and 28 satellites. L3Harris made its bids.

The company failed to win a contract for the data transport layer satellites, losing out to Lockheed Martin and York Space Systems, the latter of which is another newcomer to building satellites for the DoD. While it was still in the running for the HBTSS and tracking layer satellites, L3Harris was now 0 for 3.

Based on feedback from SDA on its transport layer bid, L3Harris refocused its bid for the tracking layer around its ability to manufacture its own commercial bus for the satellite. That in particular was appealing to SDA, said Gattle.

“That was enough to convince SDA that, yes, this was a commercial — I’ll call it a commercial-like — offering,” he said.

Return on investment

The real breakthrough — and reassurance that the company’s investments weren’t in vain — came soon after.

Last October, SDA awarded the two tracking layer contracts to L3Harris and SpaceX. L3Harris received $193 million, while SpaceX got $149 million. The selection was a surprise: Neither of the winners had built a missile warning sensor for the government before. SpaceX hadn’t even built a satellite for the government before.

While Elon Musk’s company fought its way into winning a massive Space Force launch contract last year and is working to integrate its Starlink broadband constellation with various weapons systems, no one expected it to be building missile tracking satellites for the military. SpaceX will build the satellite bus and subcontract for the actual OPIR sensor.

While L3Harris had been in the running for several missile warning satellite contracts, it had never gotten one over the line.

“A decade ago, we probably didn’t have a shot,” said Gattle. “To be honest, we were a component supplier. We would build a handful of anything that we built.”

“This is the culmination for us of a pretty big pivot in our company. We were known mostly as a weather sensor company in this particular area, infrared,” he added. “Then a couple of years ago we saw that our infrared sensors on our weather satellites could actually pick up rocket launches.”

Chris Quilty, founder and a partner of Quilty Analytics, said L3Harris has accomplished “a remarkable string of contract successes” since it entered the satellite manufacturing business only a few years ago, noting an Air Force remote sensing constellation award, among others.

”The fact that SDA awarded this contract to L3Harris is both a testament to L3Harris’ agility and an indication of SDA’s desire to open the aperture to new suppliers,” said Quilty, whose financial and strategic firm serves the space industry.

L3Harris started 2021 with more returns on its investment: Of the four companies designing HBTSS prototypes, only L3Harris and Northrop Grumman secured contracts to build their prototypes. L3Harris won a $122 million award, while Northrop Grumman got a $155 million award.

L3Harris’ journey from building weather sensors to building missile warning satellites kicked off in 2017, when the company’s technology accidentally detected a rocket launch off the Florida coast. It turns out that rocket was carrying the third satellite for the nation’s prime missile detection constellation.

There’s a certain poetry to that story. The accidental detection of a missile warning satellite being delivered to orbit inspired a newcomer to enter the field, and that company went on to win a chance to help build the U.S. military’s new missile warning architecture.

In 2017, L3Harris had ambitions and a weather sensor. In 2021, it’s a missile tracking company.

Nathan Strout covers space, unmanned and intelligence systems for C4ISRNET.