Army planners say their tiniest timekeeper is almost ready for the big time. No larger than a sugar cube, the chip-scale atomic clock (CSAC) could give future warfighters a new tactical advantage.

"In two words: continued operations," said Paul Olson, chief engineer for the U.S. Army Communications-Electronics Research, Development and Engineering Center (CERDEC) Positioning, Navigation and Timing (PNT) division. "Operations that could have been disrupted will be able to continue. The radios will work, the networks will work, electronic warfare operations will continue to work."

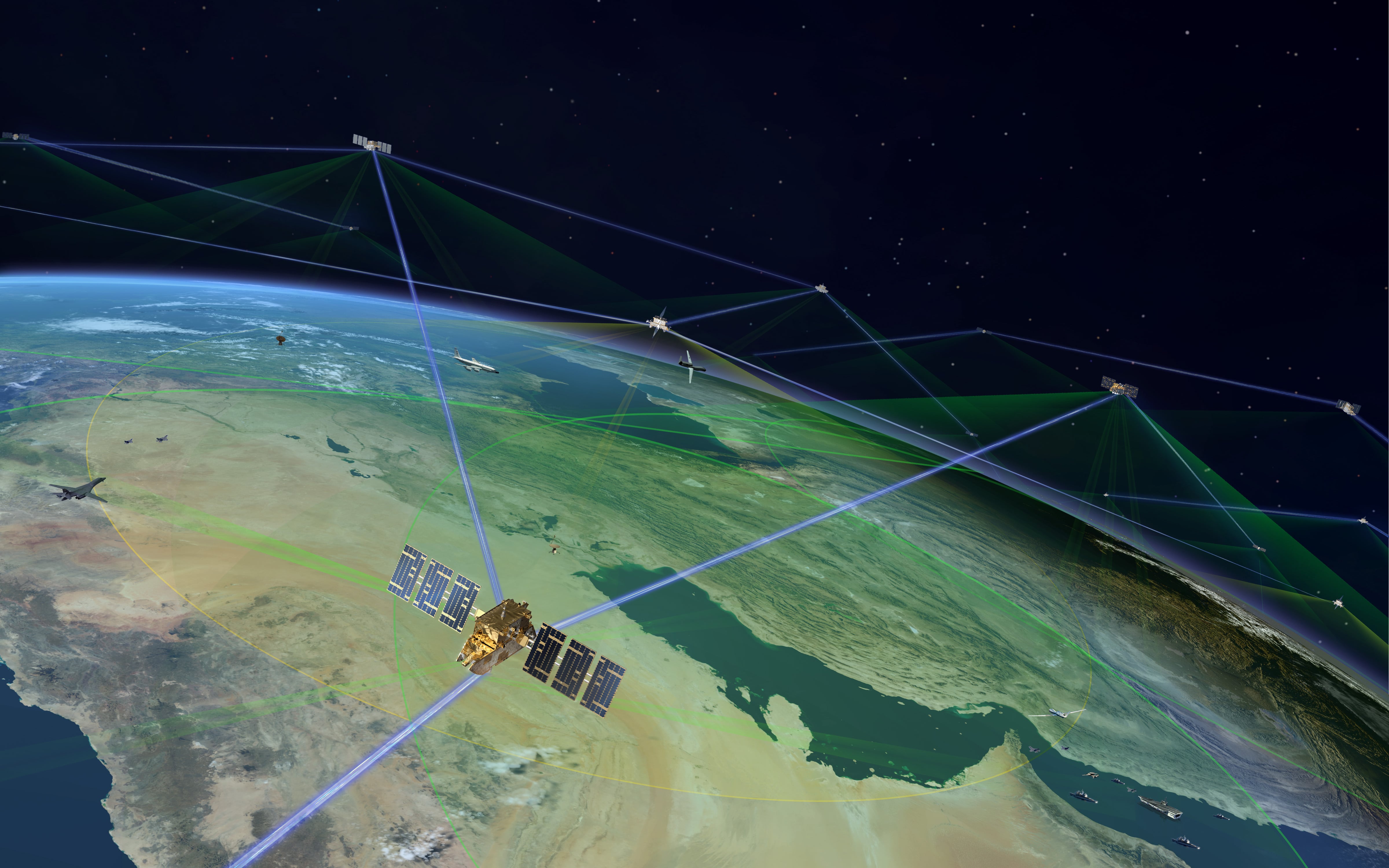

All these are in essence timekeeping functions: Radios and networks depend in part on the hyper-precise time measurements embedded in GPS signals. When GPS is disrupted by an enemy or signal is lost because of weather or terrain, these functions can break down.

Atomic clocks have helped military planners work around potential GPS loss in the past, but they have been cumbersome devices — big, rack-mounted setups weighing 50 to 60 pounds and drawing lots of power. The CSAC could offer a tiny alternative: The chips size up at approximately 15 cubic centimeters, draw little power and should cost less than $500 each by the time they enter into large-scale production.

They're not quite there yet, but CERDEC officials say they are moving the ball forward.

CERDEC first teamed with Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in 2002 to develop micro-clocks for weapons, weapons systems and the dismounted soldier. A successful prototype emerged, and in 2010 the CSAC work migrated to the U.S. Army Manufacturing Technology (ManTech) under the deputy assistant secretary of the Army for research and technology (DASA-R&T).

In 2013 CSAC was on the move again, transitioning this time to the PM PNT, where managers say they have begun the active explorations that will lead to acquisition of the devices for use in a range of mounted and dismounted systems by about 2022.

"The technology is there, and there are designs that we will start to see in the next couple of years," said John Del Colliano, PNT Integrated Systems branch chief.

While the exact nature of those applications is still under discussion, CSAC could have an impact in a range of different operations, any of which may depend on accurate timekeeping. The clocks could help foot soldiers make better use of jammers that prevent radio-controlled improvised explosive devices from detonating, for example. They could also help keep drones aloft, should GPS signal be interrupted.

PNT Senior Research Electronics Engineer Yoonkee Kim pointed to early uses by the Marine Corps, which he said is experimenting with CSACs in its Counter Radio-Controlled Improvised Explosive Device Electronic Warfare (CREW) systems. These high-power, modular, multiband radio frequency jammers are meant to deny enemy use of selected portions of the radio frequency spectrum. Like much electronic warfare technology, CREW depends on accurate timekeeping, Kim noted.

Researchers also are looking into possible nautical implementations of CSACs. They say they envision atomic clocks being used to augment sonar and positioning capabilities in underwater environments, where GPS does not function.

While CSAC's capabilities have been proven in the lab and in limited field testing, researchers say they would like to drive additional enhancements to the capability, even as they formulate potential applications for consideration by the acquisitions community. They are exploring ways to better manage noise reduction, and are looking at means to make the chips less susceptible to environmental factors, such as weather extremes.

Looking ahead, they say they envision the chip-sized clocks being embedded in GPS devices, a move that could make time-dependent applications even more reliable in battlefield conditions.