WASHINGTON — With a growing number of cyber breaches, lawmakers and outside experts are pushing to increase the role of the National Guard and National Reserve if a catastrophic cyberattack were to occur.

The idea is to create a special cyber reserve force for crises, and to do a better job of using the cyber expertise of Guard members. These recommendations come from the bipartisan Cyberspace Solarium Commission, created by Congress in 2019 to develop a multipronged U.S. cyber strategy to prevent a so-called cyber 9/11. Now, the Defense Department must evaluate the cyber reserve idea and clarify how the state-focused Guard could help with significant federal cyber events, as ordered by the 2021 defense policy law.

In such an emergency, malicious cyber actors may have attacked the power grid, for example, to cut large swaths of electricity, which could be deadly in some weather. Department of Defense cyber warriors, strained by increasing military network threats and new duties defending election integrity, would be further stressed during a potential doomsday scenario.

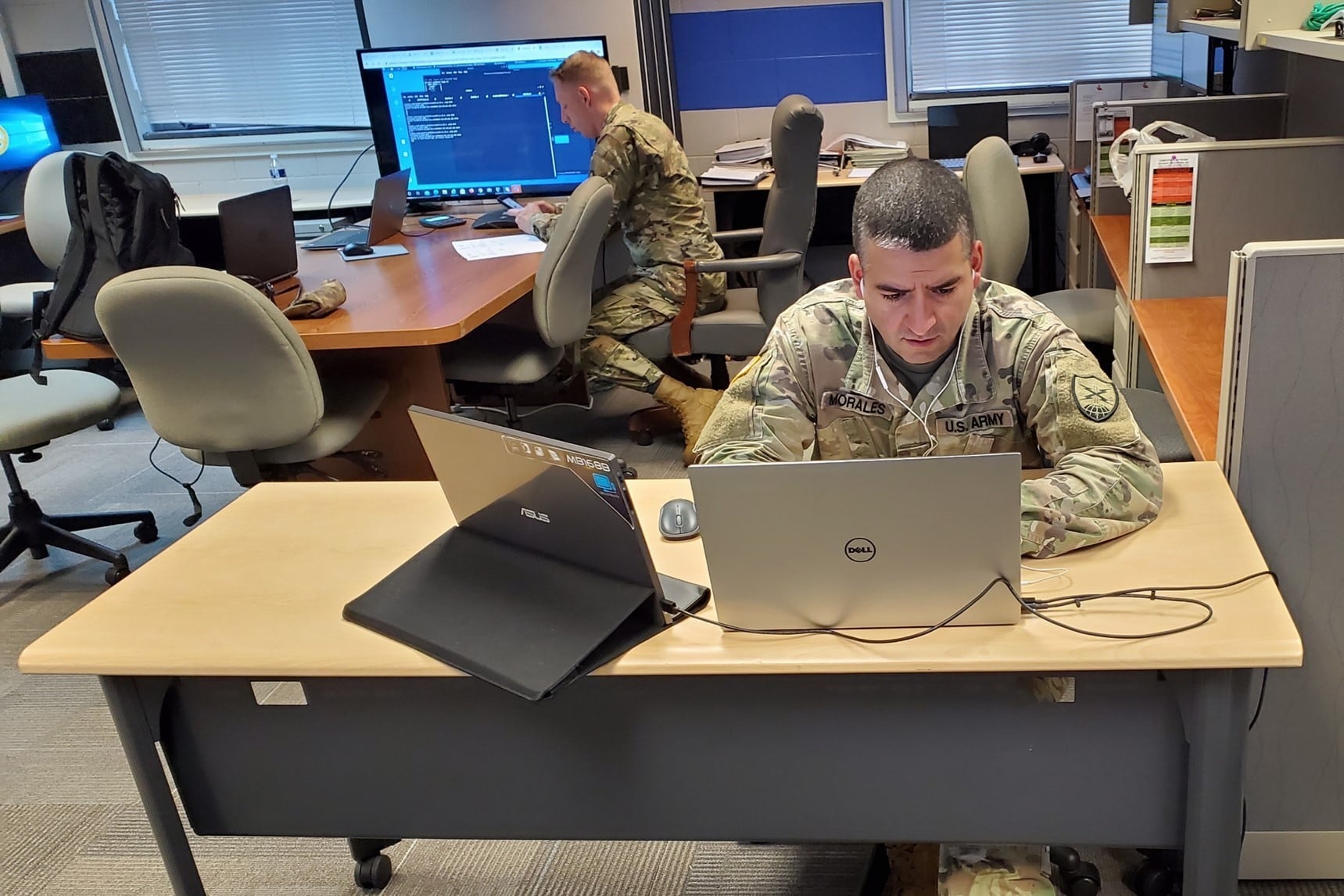

If the worst happens, cyber Guard and Reserve troops — many with beneficial skills from civilian jobs at the nations’ top cyber firms — could help repair networks, fight intruders and get systems running again. But not without changes.

RELATED

The Guard should be able to help states respond to those attacks like it does for other threats, Sen. Maggie Hassan, D-N.H., told C4ISRNET in a statement. “Especially amid the COVID-19 pandemic, we’ve seen how big of a threat cyberattacks can pose to state and local governments, schools and public health,” said Hassan, ranking member of the subcommittee that oversees emergency management.

She recently introduced legislation with Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, to clarify that the Guard can conduct cyber operations to protect vital infrastructure. “I’ve heard directly from local, state and federal leaders about the need for increased cybersecurity collaboration, and it’s clear that the National Guard can play a key part.”

With the U.S. Cyber Command workforce nearly static since its creation a decade ago, the Solarium Commission members identified the National Guard and a new cyber reserve team as top ideas to remedy federal shortfalls in staffing and expertise. Without that safety net, Americans could be cut off longer from essential services after a debilitating cyberattack.

Each military branch has reserve troops who serve under its chain of command, backfilling units on deployment or deploying themselves when needed. The National Guard has a unique role in domestic affairs. As part of the DoD, its forces are assigned to state governments for missions such as disaster response and riot control. However, these troops can be federalized — or brought under the control of the federal government — to augment active-duty forces under the Title 10 law of U.S. Code.

A cyber reserve

For the surge force separate from the Guard, the Solarium Commission said that team should be part of the National Reserve.

“This recommendation envisions a Title 10 military cyber reserve distinct from the Guard, distinct from a civilian cyber corps. This is meant to be a very specific type of reserve force,” Erica Borghard, director of the commission’s Task Force One, told C4ISRNET.

For its evaluation, the DoD will need to examine the potential for a uniformed, civilian or mixed cyber backup force.

In the National Reserve, a hodgepodge of members have a variety of cyber skills, such as strengthening systems’ protections, hunting on networks for threats and patching software vulnerabilities. Some within the Reserve’s ranks and in the private sector are concerned those skills haven’t been taken advantage of, possibly frustrating reservists and harming retention.

Many high-tech DoD initiatives don’t fit with the model the DoD uses to augment active-duty forces in the Middle East with Guard and Reserve members, said Jacquelyn Schneider, a fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford and a commission adviser.

For a cyber surge force, “we’re looking for people who need flexible work, who maybe are not going to deploy to the front forces but that we can have them augment cyber initiatives,” she told C4ISRNET.

Pentagon guidance on creative ways to use the forces as a talent bullpen would be helpful, Schneider said.

To do this, the DoD needs to better understand reservists’ skills to flex the right forces during a crisis. Some Solarium Commission members have called for kind of Rolodex or LinkedIn-type repository to help the Pentagon track reservists’ military occupational specialties and expertise, particularly because “cyber” isn’t a specialty. That job role would encompass IT work, networking, software coding, building architectures and more.

“You want to create a strategic cyber reserve and know where you would use them, how you would use them, when you would use them,” Rep. Jim Langevin, D-R.I., a Solarium commissioner, said in an interview. “That’s something you don’t want to do when the stuff hits the fan and you’ve got to plug them in somewhere. You want to have that well thought out, well planned and well exercised.”

Who does what?

The Army and Air National Guard have roughly 4,000 cyber operators between them across 54 states and territories — the only force of its kind available to governors.

The Guard has been an important resource for governors to address states’ cyber issues, from responding to ransomware incidents to securing elections from cyber threats to assisting active-duty cyber warriors.

However, experts said the roles, responsibilities and jurisdictional issues for intrastate, interstate and federal responses need clarity before a major national cyber crisis, with one source indicating there’s ambiguity about what guardsmen can do beyond assisting state governments. Though the forces have been able to respond to cyber incidents so far, the planning is for an event of unprecedented magnitude.

The Solarium Commission recommended clearing up how the federal government covers expenses for the Guard’s use in national-level operations.

Langevin said governors and the Guard need a better understanding of the authorities that would allow a governor to deploy those troops to defend critical state infrastructure in a cyber emergency.

Use of these Guard forces “has to acknowledge how it’s going to be paid for, and the states need to be prepared to do their part and pay for those costs,” he said. “We can’t always be looking for the federal government to be coming with resources like the cavalry whenever there’s an issue. There’s got to be some shared responsibility.”

Additionally, states do not turn to the Guard for cyber work in uniform ways, and capabilities vary widely from state to state, experts said. Some states have larger forces, and some pool cyber operators to reach the DoD’s standard 39-person defensive cyber protection team.

Experts said there might not be enough staff in the event of a multistate cyber emergency. Or similarly, if units from one area of the state are asked to help in another, that exposes their home region.

In the past, “the way they [states] used the Guard when it came to cybersecurity issues was really kind of state by state,” said Michael Garcia, a senior national security policy adviser at the think tank Third Way. “There’s a lot of gray in some of the guidance that’s currently out there.”

Garcia, who served as the Solarium Commission outreach director, added that some states use Guard members more than others for cyber duties, especially election security. But ultimately all sides need a uniform understanding of federal and state roles for those cyber-focused troops.

Langevin agreed: “We have to be realistic about what they can and cannot do. They can’t be everywhere at once.”

State and federal connections

The Guard already helps federal cyber forces in different ways.

For example, one step to strengthen the partnership was to create a portal to share information about malware and cyber trends. The cyber 9-line platform, named after the 9-line codes all troops use when seeking battlefield medical attention, provides U.S. Cyber Command data from Guard units to compare with information gathered in operations on networks outside the U.S. The states, in turn, gain insight into threats they might be dealing with.

With the portal information, Cyber Command’s elite Cyber National Mission Force can seek to thwart malicious action in foreign cyberspaces to eliminate a threat against a state’s systems, creating a symbiotic relationship between state Guard units and the DoD.

As a result, Cyber Command helps states bolter their self-defense, and Guard cyber warriors strengthen national security when they share potential threats with the federal team, said Col. Sam Kinch, the former National Guard adviser to the commander of Cyber Command.

For the teams that the services provide Cyber Command, the Air Force includes a mix of active-duty and Guard members — the only branch with that total force approach.

The Army has used Guard units at times to supplement Cyber Command. One such effort is Task Force Echo, a secretive team created in 2017 and billed as the largest Guard cyber mobilization. It supports the Cyber National Mission Force with offense, defense and intelligence for operations including Joint Task Force-Ares, the online counteroffensive against the militant Islamic State group.

Now it’s up to the DoD and the states to consider how the government might draw more on the Guard’s extensive cyber expertise and add a reserve force to fulfill the Solarium Commission’s vision to keep a well-organized backup cyber team on deck.

Mark Pomerleau is a reporter for C4ISRNET, covering information warfare and cyberspace.