Despite the high-tech threats facing U.S. forces, the Army continues to operate platforms and vehicles that are decades old.

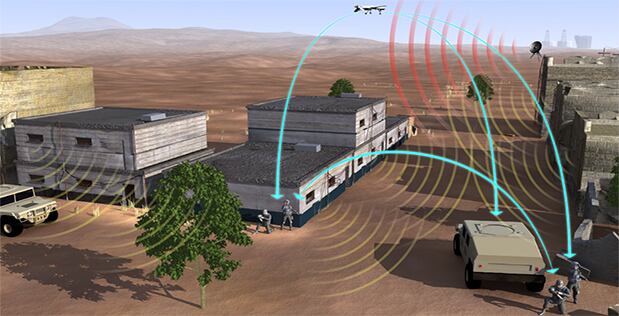

The threat from electronic jamming or electronic warfare is significantly more advanced than decades past, with adversaries such as Russia demonstrating capabilities that have worried commanders.

The Army Reprogramming Analysis Team (ARAT) works to keep legacy radars and systems relevant in this highly complex world by collecting and analyzing previously unknown threat signatures and sending updates back to systems and soldiers in the field in a timely manner.

One of the mission sets ARAT supports is radar warning receivers onboard helicopters, Jaime Compton, a member of ARAT’s engineering team, told C4ISRNET during a visit to their offices at Aberdeen Proving Ground.

Compton explained ARAT’s support process like this: Adversarial weapon systems will track Army helicopters using a radar signal to fire a missile or gun at it. ARAT, the Army and intelligence community has validated signals previously detected and identified, all of which are categorized based upon certain understood threats. If a new threat is observed, soldiers in the field can flag it and send that to the ARAT lab in which engineers will study it, analyze it to discover how it operates, conduct modeling and simulation on it, replicate the signal, develop a new mission data set software for it ensuring the fix is validated from intelligence agencies, and deliver it to the field.

More simply, the radar warning receiver is a box that must have updated software to incorporate newly observed threats in the field. This fix is delivered over SIPRNet across the ARAT Warfighter Survivability Software Support Portal, or AWSSSP, for soldiers to download themselves and upload to their mission system upon receiving an unclassified email that the fix is available.

This entire remote process eliminates the need for direct field support. In the past, field support engineers would have to go into the field, pull out cards from each individual helicopter, reprogram it and put it back in. ARAT was formed in the wake of these inefficiencies following Desert Storm.

In fact, the entire process – from receiving a new or emergent unregistered threat, to delivering the fix over AWSSSP – can be done on a short timeline. C4ISRNET has agreed to withhold that exact timeline for operational security reasons.

"Depending on how quickly this needs to field, if soldiers are in danger, ARAT is going to get it out the door…in a very short amount of time," ARAT engineering team member Jessica Guy, said.

This process is very similar to what occurred in the Cold War. In decades past when forces would deploy to a theater and observe a type of jamming signal, frequency, wavelength or bandwidth, troops would collect evidence and take it to a laboratory for analysis and countermeasure development, Josh Niedzwiecki, director of sensor processing and exploitation at BAE Systems, explained. Months later, a countermeasure or antidote would be programmed in the system and used in theater. The advances in modern software and reprogrammable radios today make this previous paradigm infeasible, he said, leading to a new shift in leveraging machine learning.

This new machine-learning concept, termed cognitive EW, enables sensors to automatically learn and understand the jamming signals, adapting techniques to minimize the jamming effect.

Compton, of ARAT’s engineering team, noted that the systems they support and sustain are 20 years to 30 years old. "It’s still a manual process of, 'there’s a signal out there, what does it look like, how can I reprogram the box to detect that signal?'" he said, adding that there are some systems that they support that were built before some of the new waveforms and jamming systems were even created. Nonetheless, the ARAT team allows their legacy systems to still be able to react against them.

During the 1960s, Compton said, a radar only did one thing. However, in 2017, they can perform hundreds of different functions at one time.

This can include tracking, searching while tracking, firing missiles, jamming, or duping forces into thinking they’re doing one thing but they’re actually doing another. While the radar receiver aboard an Army helicopter might not be able to detect or make sense of these new waveforms or functions initially, the work done by the engineers at ARAT upgrade the legacy systems and radars so they can continue to detect the threats in the field despite the apparent technology paradox.

With constrained resources and budgets, the military will be increasingly reliant on legacy systems, despite the proliferation of commercial and adversarial technology. According to officials, work by the Army’ sustainment community seeks to ensure systems last.

As a result of such technology upgrades, insertions and improvements, many legacy systems "are not the same systems that we started 30 years ago," Frank Zardecki, Deputy Commander at Tobyhanna Army Depot, told C4ISRNET during a visit to their facility last year. For example, an "Army Chinook aircraft [is] going to be flying when it’s 100 years old…the only thing original in that is the airframe. The engine, the avionics have been upgraded."

Automated testing

One of the capabilities that has revolutionized what ARAT’s team is able to do is the use of automated testing.

In the past, testing and analyzing of new threat signatures had to be done manually involving testers and analysts running a variety of evaluations for hours. Now, with software automation, a computer runs the tests and analyzes the results, Compton said.

Instead of having folks sitting there for hours, Compton said they are free to conduct analysis on other programs, or update their models and simulations.

While ARAT’s process and mission has not changed, what has is the automated testing, which has borne out significant cost avoidance and time saving, officials said.

Mark Pomerleau is a reporter for C4ISRNET, covering information warfare and cyberspace.