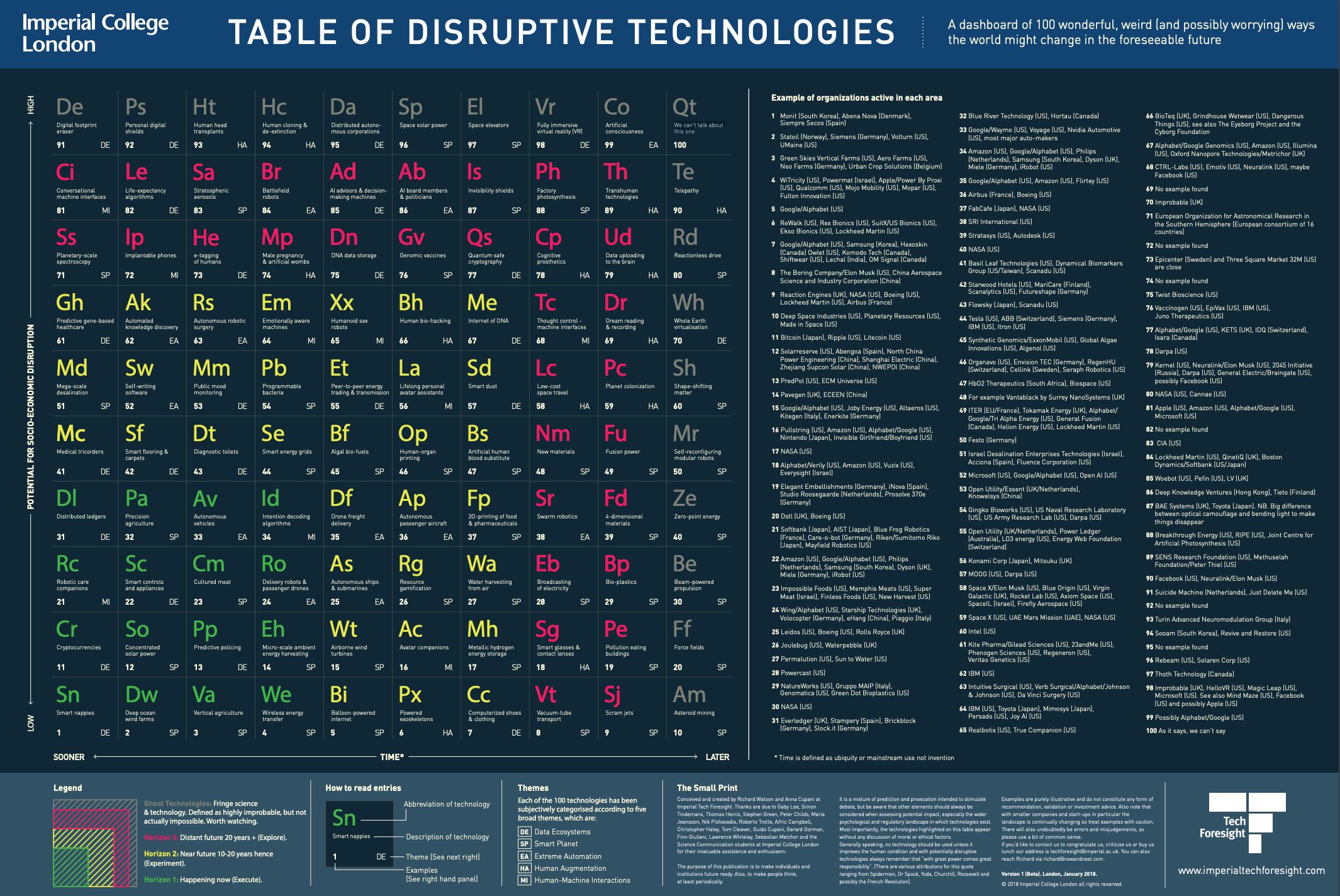

Telepathy. Data uploading to the brain. Even humanoid sex robots. These are among the ideas that exist on a periodic table of disruptive technologies, a new visual guide that predicts what will alter human existence in the coming years.

Created by Imperial College London, the table identifies what is set to change societies in the short term (smart controls and appliances), as well as fringe ideas that are decades away from existence, if they will exist at all (think force fields.)

Yet the disruption could turn disastrous without proper data-security standards, according to one of the chart’s creators, Richard Watson, the futurist in residence at Imperial College London.

“There is very little here that is not in some way digital and connected, which makes it vulnerable,” Watson said.

“Any kind of internet-of-everything device doesn’t really work if you haven’t got common standards — if Apple isn’t sharing with Google and the French aren’t sharing with the Germans.”

Experts have long expressed concern about the lack of data standards for internet-connected devices. There is no international standard for data security. And U.S. government oversight of internet-connected devices is spread across at least 11 different federal agencies, according to a 2017 Government Accountability Office report.

“As new and more ‘things’ become connected, they increase not only the opportunities for security and privacy breaches, but also the scale and scope of any resulting consequences,” the report said.

And there has been a flurry of cyberattacks using internet-connected devices. Some hackers are exploiting smart devices as an intermediary to attack computer networks, the FBI warned Aug. 2. Ninety-three percent of respondents told Armis, a security platform, in an August survey that they expected governments to exploit connected devices during a cyberattack.

The Imperial College London chart offers a further glimpse at how important it may be to create these common regulations by imagining a wealth of potential breach points. Watson listed some of the table’s future technologies that could be hacked.

“Smart controls and appliances.”

Hackable.

“Autonomous robotic surgery.”

Hackable.

“Autonomous ships and submarines.”

Hackable.

“One of the issues with the stuff on here is that it relies on extremely good data security,” Watson said.

The problem with having a developing ecosystem without global standards is that a single vulnerability could allow access to more than one network, and government officials and businesses are currently taking a strategy of letting the private sector debate how, or if, to regulate itself when it comes to internet-connected devices.

One piece of bipartisan federal legislation, the 2017 Internet of Things Cybersecurity Improvement Act, mandates that “devices purchased by the U.S. government meet certain minimum security requirements," but it has stalled in Congress.

As a first step, manufacturers should collaborate to establish device security baselines, Jing de Jong-Chen, general manager for global cybersecurity at Microsoft, said during a June conference hosted by the Woodrow Wilson Center, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank.

One private solution is a set of common guidelines developed by the IEEE Standards Association, an industry trade organization. The trade association’s voluntary standards is evidence of a fear of government regulation that the private sector is openly hostile to. During the June event, the idea of government regulation of smart devices was laughed at by private sector officials in the room. But that laughter may have been premature.

In September 2018, California Governor Jerry Brown approved a bill that requires companies to install connected devices with “a reasonable security feature” protecting it against unauthorized access. The bill means that the periodic table of disruptive technologies may eventually be impacted by a modicum of public regulation, although it is not clear if that will be effective.

Not making it any easier is that no amount of planning can compensate for every technological innovation. For example, when it comes to the most disruptive future technology, the chart is secretive. In position 100, predicted to be the most innovative idea, the chart says it is too dangerous to publish. “We can’t talk about this one,” it reads.

In this instance, however, a potential security risk is averted. When asked if this technology is the one that will literally “break the internet,” Watson is forced to make a confession: “It’s a joke. It’s just us dodging the ball because we couldn’t think of what to put there.”

Justin Lynch is the Associate Editor at Fifth Domain. He has written for the New Yorker, the Associated Press, Foreign Policy, the Atlantic, and others. Follow him on Twitter @just1nlynch.